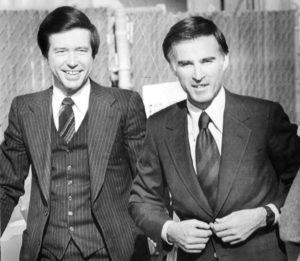

Editor’s note: Gray Davis, the 37th Governor of the State of California, served as chief of staff to Jerry Brown during his first two terms as governor (1975-1981). We asked Gov. Davis to write a foreword to our lengthy oral history with Brown, which we are pleased to share with you below. Click here to see Davis’s essay in the context of Brown’s oral history. See more resources on the Jerry Brown oral history.

*******

Governor Edmund G. (“Jerry”) Brown was the longest serving governor in California history, and one of the most consequential. First elected in 1974, he championed a major solar initiative (first-ever tax incentive for rooftop solar), and signed legislation prohibiting any new nuclear power plants in California until the federal government certified a safe way to dispose of nuclear waste. To this day, the Federal Government has yet to do so and no further nuclear plants have been approved.

Governor Brown also negotiated and signed the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975, a first of its kind in California and the Nation. Even today, it remains the only law that creates and protects the rights of farmworkers to unionize and collectively bargain. None of the other 49 states has been able to pass similar protections for some of the most vulnerable workers in our country.

In March of 1976, Jerry announced his run for the presidency and won primaries in California, Maryland and Nevada, and accumulated the second highest number of votes going into the convention (2,449,374). His late entry into the 1976 democratic presidential primary precluded him from catching Jimmy Carter, who accumulated the requisite amount of delegates to secure the nomination and become president.

Jerry Brown left office in 1983 and did not return to the governorship until 2011, 28 years later, making him California’s youngest, oldest and longest-serving governor. His third and fourth terms featured a remarkable turnaround in the state’s financial standing. He inherited a $27 billion deficit but left office with a $29 billion surplus ($14.5 budget surplus and a $14.5 billion “rainy-day fund”).

In an effort to restore the State’s fiscal stability, Jerry sponsored and campaigned for the passage of Proposition 30, a voter-approved tax increase that raised $6 billion. Tying his fiscal and environmental stewardship together, in 2012 Jerry signed into law the first in the nation government run cap-and-trade program, creating in excess of $9.3 billion to fund emission reductions and programs that protect the environment and promote public health.

He left the Governor’s office and public life in early 2019, enjoying a higher approval rating than any governor since Ronald Reagan.

To understand Jerry’s expansive worldview and insatiable curiosity, it is helpful to take stock of where he has been and what he has done. The son of a Governor, he lived in the Historic Governor’s Mansion, attended parochial high school, studied at Santa Clara University, joined the Sacred Heart Jesuit Novitiate seminary, received his Bachelor’s Degree from UC Berkeley and his law degree from Yale. In addition, Jerry has practiced private law at Tuttle and Taylor, was elected to the Los Angeles Community College Board of Trustees, California Secretary of State, California Attorney General and four times as Governor of California. He has run the State Democratic Party, served as Mayor of Oakland and ran three times for president. He’s traveled the world, studied Buddhism, and worked with Mother Teresa at her Home for the Dying in India.

When I was running for governor, people asked me what does it take to be a successful governor? My answer (in jest) was “rain in the north and a strong economy.” Obviously, the governor cannot affect the weather. As for the economy, state tax incentives can only affect the economy on the margins. In the main, economic expansions and recessions are a result of the business cycle and function largely outside the Governor’s control.

But that is not how the public sees it. They give great credit to a governor when the economy is improving, but hold him fully accountable when the economy is in recession. Every governor from Ronald Reagan has experienced a slowdown or recession of some type. Reagan, Jerry Brown in his first two terms, Deukmejian, Wilson, myself and Schwarzenegger have experienced the ups and downs of the economy.

But when Jerry Brown was inaugurated for the third time in 2011, the economy turned positive and remained positive for his entire eight years.

That was a great relief to the public whom had experienced an unemployment rate of 10%, the loss of thousands of homes to foreclosures and financial downgrades, as conditions deteriorated in California.

This economic rebound was a critical factor in rescuing California from nearly a decade of deficits; however, it took more than good luck to turn California around. Jerry Brown brought the fiscal discipline necessary to turn the corner. He had reached out to almost every legislator as soon as he was elected for the third time, explaining that the path of more borrowing and larger deficits was not sustainable.

Despite hundreds of hours of collaboration with the legislature, their initial budget was a disappointment to him and was clearly not in balance. After much deliberation he decided to do something that has never happened in California: he didn’t just veto parts of the budget as most governors in the past had done, he vetoed the entire budget!

Sacramento was in shock!

After a number of heated meetings, he and the legislature produced a second budget with numerous reductions that was in balance, and put California back on the path back to solvency. As a result of that budget and previous cuts, some 30,000 teachers had been laid off, many classes had been canceled as well as almost all after school programs in California. In his 2012 budget, the governor and legislature restored some, but not all, of the cuts made during the previous three years.

That same year, the Governor gambled that he could persuade voters to pass Prop 30, which generated $6 billion additional dollars that paid for these new teachers and professors and restored many of the classes that had been eliminated in previous years. In fact, the voters believed Jerry Brown when he said California could not cut anymore. They believed him when he said that most of the taxes would fall on the wealthy and that Prop 30 would put California back on the path to greatness.

The voters passed Prop 30 and gave California a fresh start.

A governor without Governor Brown’s discipline and well-known frugality might not have convinced California voters to increase taxes by $6 billion. Without Jerry Brown’s leadership, cooperation of the legislature and the strong economy he inherited, California might still be waist deep in deficits rather than the 5th largest economy in the world. Jerry Brown exited the stage in January 2019. By the time he left, California had new problems, including homelessness and poverty; but he and the legislature solved the problems they inherited by righting California’s finances and helping rebuild its economy.

Frugality and Good Fortune:

Before Governor Brown was inaugurated in 1975, he told me he did not want to be driven in a limousine, but preferred instead a car normally assigned to a legislator or cabinet officer. When I conveyed that message to the director of general services, he told me they had 1974 Plymouths available in three colors: gold, white and blue. I opted for blue, envisioning dark blue or royal blue.

After the Governor delivered a 7-minute inaugural address, we started walking across Capitol Park for our trip to San Francisco. There was only one car waiting for us – and it was not the dark blue Plymouth I anticipated but a powder blue Plymouth! No California governor has ever been a driven around in a powder blue Plymouth. I was beyond embarrassed!

“Is that my car?” Governor Brown asked. “I’m afraid it is,” I replied.

But to the Governor’s great good fortune, the public warmed up to the idea of a powder blue Plymouth; they began to take pride that their Governor had chosen a less expensive and less imposing looking car as his official vehicle. By the end of Jerry’s second term, the blue Plymouth became almost as recognizable as the Governor.

Another example of the governor’s frugality occurred about three months into his administration. We were just finishing our morning meeting, when I mentioned to the governor that I had asked General Services to come over and not replace, but repair a 10-inch hole in the rug adjacent to his desk. “Why would you do that?” he asked. “Because it’s unseemly to have a hole in the governor’s rug.” The Governor answered: “That hole will save the state at least $500 million, because legislators cannot come down and pound on my desk demanding lots of money for their pet programs while looking at a hole in my rug!”

That told me not only was the governor genuinely frugal, but that he also understood the power of his frugality to fight off excessive demands in the budget. It gave him the moral authority to ask for big cuts when the state was $27 billion in debt at the start of his third term, and the courage to veto the entire budget when they did not make those cuts.

Jerry Brown was the best and possibly the only leader who could overcome the challenges that California faced in 2011 and lead the state back to the 5th largest economy in the world.

When he walked out of his office for the last time in January 2019, only the United States, China, Japan and Germany had larger economies than California.

By Governor Gray Davis (Ret.), 37th Governor of California